Measles: The Govt's Fear Factor

How exaggerated health stats are used to alarm the public

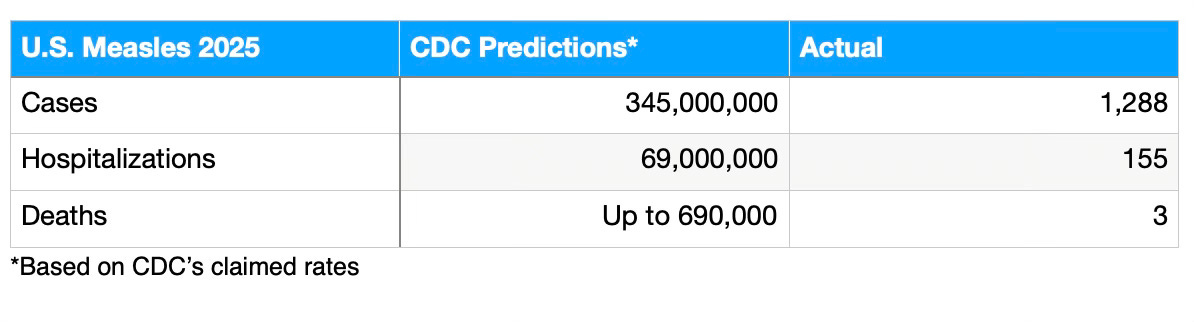

If measles were truly as contagious and deadly as the government claims, nearly all of us would all have been infected so far this year, and up to 680,000 of us would die from measles in 2025.

The measles example highlights a longstanding pattern of public health officials and government exaggerating risks, misleading, and manipulating narratives to advance agendas.

As a result, public health officials erode public trust— then blame others when people doubt or disbelieve government advice.

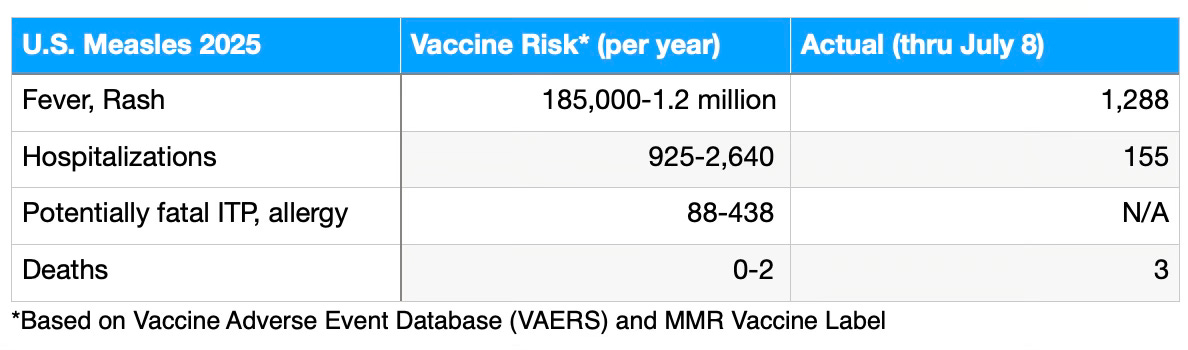

And wait until you hear how many people are injured by MMR vaccine each year compared to those hurt by measles.

The government and public health officials have long painted measles as a viral boogeyman: a disease so contagious it could sweep through communities like wildfire, leaving a trail of hospitalizations and deaths!

Official claims state that each person infected with measles can quickly spread the disease to 12–18 others, with up to a 0.2% death rate and up to 20% hospitalization risk! Most people don’t mention the asterisk to those claims, which we’ll discuss at length.

But these dire warnings are an alarmist mirage. They assume a world that doesn’t exist. Where nobody is vaccinated or naturally immune—a scenario as outdated as a cassette tape player.

In today’s real-world environment, where most Americans have immunity from vaccines or prior exposure, measles’ contagiousness and danger are far less apocalyptic.

Yet the government and public health officials haven’t adjusted their outlandish estimates and claims.

By failing to factor in modern immunity and medical care, the government’s rhetoric inflates fear, skewing public perception and policy.

Just as shocking: even when scrutinized in a pre-vaccine world, their frightening claims don’t hold up.

The indisputable fact is that in today’s real world, measles injuries in the U.S. are dwarfed by injuries from the MMR vaccine for measles, mumps, and rubella. Yet this risk vs. benefit is never calculated or even acknowledged, as the government pushes out dire warnings and bad statistics.

Read on for details.

The Measles Fallacy: A World That Doesn’t Exist

The Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC’s) oft-cited statistic is that one person with measles quickly infects 12–18 other people. That relies on the basic reproduction number (R₀), a measure of contagiousness in a fully susceptible population.

There are two fatal flaws with this assumption. First, this scenario assumes there is currently zero immunity in the U.S. population, as if vaccines and natural exposure never happened. Second, the government’s cited statistics are simply incorrect— even for a zero-immune population— and have never been applicable in the U.S.

As of 2023, about 90.8% of children aged 19–35 months had at least one dose of the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine, and 93.1% of adolescents were fully vaccinated with two doses. In addition, many adults born before the 1989 two-dose recommendation have natural immunity from childhood infections or single-dose vaccination.

In all, a 2019 study estimated 93–95% of the U.S. population is immune to measles, through vaccination or prior infection.

Obviously, this high immunity rate drastically lowers measles’ actual contagiousness under real-world conditions. In a population with 93% immunity, the number of new infections per case drops to a much smaller rate: each person with measles may infect 1–2 people, not 12–18. Outbreaks tend to fizzle out quickly or have limited spread.

This year’s measles outbreaks illustrate this. If measles were as contagious as the CDC statistics imply, the first case in the West Texas outbreak would have resulted in the entire U.S. population being infected in roughly 90-100 days. If true, since the first case was reported on January 23 this year, the whole country would have caught measles by the end of April.

But instead of 345 million people infected, we’re in mid-July and have a relatively meager 1,288 confirmed cases across 38 states and Washington D.C.

The CDC statistics on hospitalization and death are as equally ludicrous.

The CDC warns that up to 20% of measles cases require hospitalization, 0.1–0.2% end in death, and that complications like pneumonia or encephalitis (brain damage) affect 5–10%. Couple that with the CDC’s stated infection rate for measles, and that would add up to 69 million hospitalizations in the U.S. for measles so far this year from the initial Texas case.

Additionally, 17-34 million people would have suffered complications like pneumonia or encephalitis. The CDC's estimated death rate of 0.1–0.2% would mean 345,000–690,000 of us would die.

No Good Explanation

Ask where the government gets its alarmist figures, and some say the data is extrapolated from the pre-vaccine era of the 1950s and 60s, or from developing countries with limited healthcare.

But even that doesn’t fly.

In the U.S., peak measles outbreaks occured in 1958 and through the early 1960s. There were a half million cases up to a high of about 763,000 reported annually, and 400-500 deaths. The CDC retrospectively jacked up those actual infection numbers by as much as 800%, with much higher estimates of 3-4 million cases. That’s because the CDC assumes that most cases went officially unreported because they were so mild. “Not all cases were seen by doctors or reported, especially when symptoms were mild,” explains one health authority.

That’s a message rarely if ever told by the government: that their own statistical models assume the vast majority of measles cases are mild. This is crucial information if one is to compare measles risks to vaccine risks. More on that in a moment.

Moving ahead: if the U.S. had, on the high side, 3–4 million cases a year and 400–500 measles deaths among them at the peak. That’s a “case-fatality rate” (CFR) of 0.01–0.015%. So the CDC’s claimed measles case fatality rate today of 0.1–0.2% is 6.67 to 20 times higher than what we actually experienced in the real world at the peak, before vaccination, and when medical care wasn’t as good as it is today.

So why does the U.S. government mislead us with far more dire scenarios? And where do they get the outlandish figures that don’t apply to America today—or even in the late 1950s?

I asked the “X” Artificial Intelligence tool “Grok” to take a stab at an explanation. It stated that “the CDC’s 0.1–0.2% case fatality rate likely stems from global data, statistical models, and an emphasis on severe outcomes in vulnerable populations, rather than U.S.-specific historical data from the 1950s–60s, which showed a much lower case fatality rate. This discrepancy suggests the CDC’s estimates could be critiqued as an overstatement to underscore vaccination importance…they don’t align with the U.S. pre-vaccine era.”

Measles in Today’s Real World

So we’re left with the critical question: How contagious is measles in 2025 America, with 93–95% immunity?

Not very.

In vaccinated communities, scientists say the number of people infected by one measles patient falls below 1. One persontypically infects less than one person on average—or nobody. This means outbreaks die out long before the CDC’s dire predictions are realized.

Even in unvaccinated clusters, like the Mennonite community in Gaines County, Texas, the spread of measles is limited. One case in a 90% vaccinated school might infect one or two susceptible kids before stopping, not the 12–18 that the CDC claims.

This year, the individual outbreaks have stayed localized despite 27 separate clusters nationwide.

The Hypothetical Apocalypse

The CDC’s no-immunity model is theoretical nonsense. The government’s numbers are wildly exaggerated for today’s context.

Even in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with no vaccine, annual cases hit an estimated high of 3–4 million, not the entire population of 175 million, because of natural immunity and containment.

Why the fearmongering? The CDC aims to boost vaccination rates, which fell to 92.7% for MMR among kindergartners in 2023–2024, below the government’s desired 95% “herd immunity threshold.”

This exaggeration distorts policy and trust. Mandates, school exclusions, and ads lean on worst-case scenarios, sidelining the truth: the measles real-world lack of contagiousness and rarity of complications due to modern medical care. If impact estimates reflected immunity and modern medicine, measles would look manageable, not apocalyptic.

Vaccine Risk vs. Measles Risk

With the government distorting medical reality, it become impossible for ordinary people to get a realistic idea of the risk-benefit ratio when it comes to getting the MMR vaccine for measles, mumps, and rubella.

One could argue that the CDC’s misinformation, coupled with its failure to disclose or factor in vaccine risk when promoting the MMR vaccine with one-sided propaganda, means parents are not able to give true “informed consent” when it comes to vaccination. Informed consent requires that the patient (or his parents) know and understand the risks of getting the disease measured against the risks of getting the vaccine.

A lesson that transcends this individual case: when public health officials decide they want to scare you with a disease in order to promote vaccination, they will use wild estimates, manipulated data, anecdotal reports, and unverified statistics. However, when they want to cover up the risks of vaccination, they obfuscate, accuse, and claim that those statistics are unreliable or unverified.

The facts are clear, though, if you know where to look. Whether considering the MMR vaccine’s label or data from the federal Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the MMR vaccine is causing far more illnesses than measles is this year—or any other year since the vaccine came out.

We can look at a few examples of adverse events acknowledged to be caused by the MMR vaccine: fever, rash, seizures, allergic reactions, measles inclusion body encephalitis (MIBE)—potentially fatal in immunocompromised children—and Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP), a blood disorder where the immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys platelets.

Based on VAERS data, approximately 185,000–740,000 children per year experience mild side effects like fever or rash from the MMR vaccine, 925–1,233 may have seizures triggered by high fever that requires hospitalization, and 438 may face other serious outcomes like life-threatening allergic reactions or ITP.

The MMR vaccine label paints a similar picture. For children getting the recommended two doses, each year 10-30% or 400,000 to 1.2 million kids develop a fever or rash. About 2,000 to 2,640 are hospitalized with fever-induced seizures. Eighty-eight to 248 children suffer ITP or severe allergic reactions. And the fatality rate assumes there are up to two deaths from MMR vaccine per year.

The CDC and other vaccine industry advocates will argue that injury statistics like these are to be dismissed and are overstated, speculative, and unproven. But by now you can see the dichotomy in how they accept and invent scary disease statistics, and represent them as fact, but frequently dismiss or question statistics on vaccine injury.

And there is every reason to believe the actual MMR vaccine safety profile is worse than stated. We know that there is institutional minimization of vaccine risks. Meantime, nobody is tracking many long term outcomes for vaccine injuries. For example, no large-scale, systematic studies by the CDC, vaccine manufacturers, or independent researchers routinely track MMR-vaccinated children for 10 years and beyond to assess subtle outcomes like learning disabilities after vaccine-induced seizures, or chronic immune issues.

Additionally, the reported risks of the MMR vaccine do not include potential interactions with other vaccines administered to children, which could exacerbate adverse effects. Therefore, the documented side effects likely represent a conservative estimate of the true impact of multiple vaccinations.

So while serious measles cases are concerning, by any factual account, the number of children affected by vaccine side effects significantly exceeds those infected with the disease.

Unvaccinated Unfairly Blamed

Many have mistakenly stated that, until this year, measles hadn’t been seen in the U.S. since 2000.

This widespread misimpression is understandable since the government declared measles was “eliminated” in 2000. The CDC’s designation that measles was “eliminated” simply means there was no continuous or endemic transmission of the virus for at least a year. Since then, there have been cases every single year in the U.S. but all of the outbreaks started with someone infected overseas (or north or south of our border) who then came here.

Although popular propaganda blames measles outbreaks on unvaccinated groups like the Amish, unvaccinated people do not spontaneously generate measles. When measles circulates, it’s beause the virus was brought in by a foreigner or U.S. resident who visited a foreign country.

For example, in 2019, there were 1,274 cases of measles in New York. That outbreak was sparked by travelers from Israel. In 2014, 667 cases in Ohio’s Amish country were traced to missionaries from the Philippines. The 222 cases across 17 states in 2011 were also tied back to imports, not local origins. A 2024 cluster of 57 cases in Chicago was linked to an illegal immigrant shelter. And, yes, the current 2025 spike began with an unidentified traveler who had been in a foreign country. All of this demonstrates that measles doesn’t just “pop up” here—it’s always an unwanted souvenir from abroad.

The vaccine-disease conundrum

Now to play Devil’s Advocate.

What happens if people stop vaccinating because they rightly see that the risk of the MMR vaccine in today’s environment is greater than the risk from measles?

Eventually, if fewer people get vaccinated, the equation likely changes. More people would start getting measles, initially brought in from other countries. There would be a larger pool of non-immune people to spread it. And while the infection rate might never reach the fantastical heights that the CDC claims, it would steadily inch up. At a certain point, the script would flip and it’s likely that more people would become ill from measles than the vaccine, at least in terms of immediate effects.

So is it wrong for the CDC to scare and mislead people to avoid this scenario?

Yes.

No matter the goal, it is never appropriate for public health officials whom we pay to mislead us for what they may argue is a noble goal. One reason is because their judgement has so often proven to be impaired by influence from the pharmaceutical industry.

Another reason is because without the full facts, we are missing opportunities for improvement. For example, if more attention were paid to MMR vaccine side effects, there might be pressure to find ways to minimize them and make the vaccine safer for all. There might be better recognition of adverse events with early intervention and better treatments developed to avoid serious illness. We might be able to identify what factors make some children more susceptible to the side effects.

This could lead to a scenario where there are safer vaccinations, more people are willing to give them to their kids, fewer vaccine injuries result, and measles is kept in check.

But no such initiatives can take place when vaccines are falsely portayed as infallible, and rational question are discouraged as “anti-vaccine.”

Conclusion: Fear Over Facts

Measles is no picnic—fever, rash, and occasional serious complications deserve attention. But the CDC’s claim of 12–18 infections per case and dire outcomes assumes a fantasy world without vaccines, immunity, or modern hospitals.

In 2025, with 93–95% immunity, measles spreads slowly: 1–2 new cases per person with outbreaks remaining self-limiting and dying out.

The current count of 1,288 cases with three deaths pales against the CDC’s hypothetical 680,000 deaths (if their zero-immunity statistics are played out). The government’s nightmare that extrapolates to one person infecting 340 million of us in 10 weeks hasn’t happened. By hyping inaccurate stats, the CDC risks “crying wolf,” undermining trust when real threats emerge.

If the CDC prioritized public health and transparency over vaccination advocacy, it would publicize detailed MMR adverse event rates alongside measles risks, adjusted for modern U.S. healthcare and historical context, to enable true risk-benefit analysis. It would focus on the logical goal of constantly improving vaccine safety and effectiveness.

The CDC’s current 0.1–0.2% measles case fatality rate estimate, 6.67–20 times higher than the 1950s–60s, paired with limited emphasis on vaccine risks, suggests a narrative favoring compliance over clarity. It drives skepticism and hinders public trust.

Best comprehensive review of the measles vaccine controversy!!

Official claims aren't worth the paper they are printed on.